Why is it so difficult to commit information to memory after a brain injury?

When we talk about memory, one of the things that's important to remember is that memory's not a single thing. Memory has a number of stages. One is learning, the way we get information, whether that's seeing it or hearing it or feeling it since all of those are modes of learning. Once information is presented, the brain then needs to represent it and figure out what is that pattern of seeing or hearing or feeling or combinations of those things?

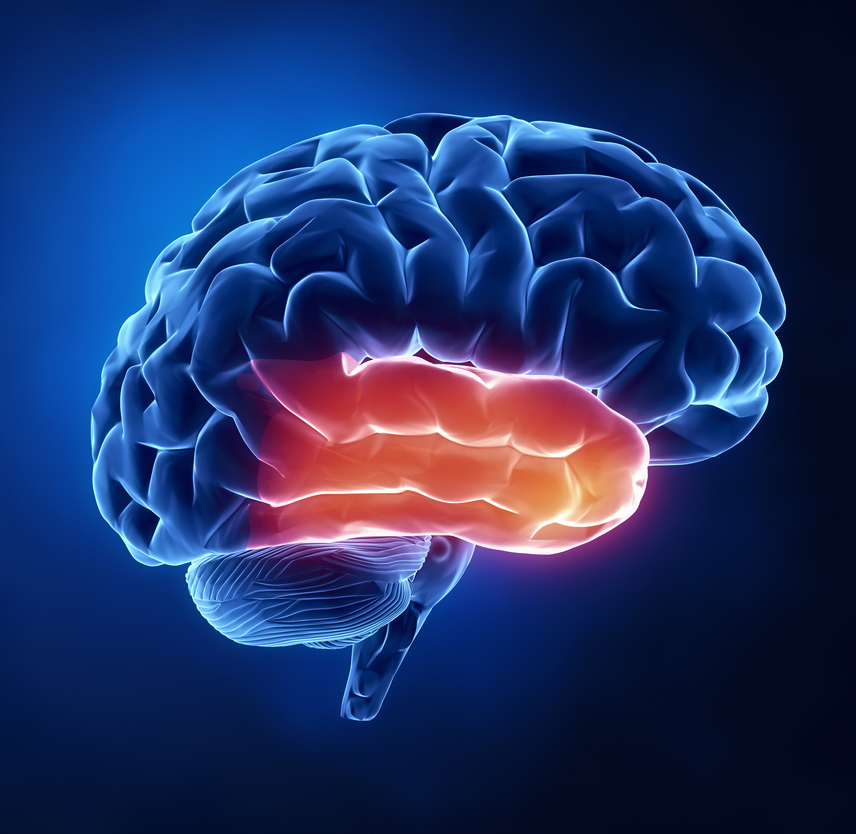

Then it can begin to commit it to those structures in the brain that help us make sense of it. Once that's been done – we call that processing coding – that pattern becomes, to use the language of the neuroscientists, consolidated, meaning it goes from simply being represented and encoded – a picture in the brain of what it is – to something that becomes there long-term.

That network is available to be activated again at some point in the future. All of that would be the initial process of learning new information and beginning to lay down a memory. Later on, with that network having been consolidated and made stable, your frontal lobes or any part of that network, if it comes online, a sound that is familiar, a sight that is familiar, a feel that is familiar – something that's been in that network from the start, can turn it on. You could also turn it on because you're asked to turn it on and think about it and get that network acting. We call that memory retrieval.

Learning, encoding, consolidation, and retrieval are all different parts of the memory process. Depending on where we are in the brain injury cycle, all of those can be disturbed. So early after brain injury, the problem tends to be learning, one or more of the modes of learning – vision, hearing, feeling, etc. is compromised by the injury. Or, encoding and consolidation. If you can't pay attention, you're not going to encode.

If you're so confused that you can't actually hold onto information long enough, you're not going to consolidate it. And late after injury, those two processes, encoding and consolidation, may still be impaired, but the real trick is then getting it when you need it, retrieving it. So laying down new information and then getting it out when you need it become the chronic problems for people with injuries.

Related Resources

- Memory and Brain Injury: Resource Section

- Coping with Thinking & Cognitive Symptoms

- Cognitive Problems After Traumatic Brain Injury

- Where Are My Keys?

- Why So Many Questions?

- Now What Did I Come In Here For? Strategies for Remembering What You’re Looking For

- Memory and Brain Injury: Resource Section

- TBI 101: Memory Problems

- Why Is It Difficult to Learn New Things After a Brain Injury?

About the author: David Arciniegas, MD

Dr. David Arciniegas is a psychiatrist in Gunnison, Colorado and is affiliated with TIRR Memorial Hermann. He received his medical degree from University of Michigan Medical School and has been in practice for more than 20 years. He is one of 2 doctors at TIRR Memorial Hermann who specialize in Psychiatry.

Comments (1)

Please remember, we are not able to give medical or legal advice. If you have medical concerns, please consult your doctor. All posted comments are the views and opinions of the poster only.

Anonymous replied on Permalink

Perhaps brain injury programs and leadership will address the repeated acquired TBI from the electrical mechanism of trauma around the use of ECT. Product liability suit that is now national around the devices used have proved this in the CA courts. These repeated TBI can number into the double and triple digits for great profits. Dr. Bennett Omalu famous for findings of CTE in the NFL head injuries is now on written record stating the same is anticipated in ECT patients. See site ectjustice.net and ectjustice.com. Some patients now have damages in medical records tied to ECT and are entering TBI programs for help. We need professionals to address this harm and provide acknowledgment and assistance as all other TBI patients receive.